If music is the food of love, it is also the soul of pageantry. Pomp and circumstance need stirring aural accompaniment to come alive, and nowhere does a period musical score vivify and enhance spectacle more impressively than in the riotous wonder of the Esala Perahera, the annual ten-day medieval pageant held in Sri Lanka’s hill capital, Kandy.

Kandy’s Esala Perahera (literally “July-August Procession”) dates, in its present form, from the last quarter of the 18th century, when it expressed royal homage to the Sacred Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha, enshrined in the temple known as the Dalada Maligawa, and to the four guardian deities of Sri Lanka: Katha, Vishnu, Kataragama and Pattini. Yet the Sri Lankan people have celebrated pageants to honour the Sacred Tooth Relic, the palladium safeguarding the nation, ever since it was brought to the island in the 4th century A.D.

Not all perahera sound is strictly musical. The start of the pageant used to be heralded by the boom of a 17th century cannon, a trophy captured from an invading Dutch army. (Old British colonial records mention “gin-galls”, or muskets, being included in the pageant, probably for salutes and signals.) Since an oversized charge of gunpowder shattered the Dutch cannon in 1959, a fireworks rocket has given the starting signal.

Kandy’s Esala Perahera (literally “July-August Procession”) dates, in its present form, from the last quarter of the 18th century, when it expressed royal homage to the Sacred Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha, enshrined in the temple known as the Dalada Maligawa, and to the four guardian deities of Sri Lanka: Katha, Vishnu, Kataragama and Pattini. Yet the Sri Lankan people have celebrated pageants to honour the Sacred Tooth Relic, the palladium safeguarding the nation, ever since it was brought to the island in the 4th century A.D.

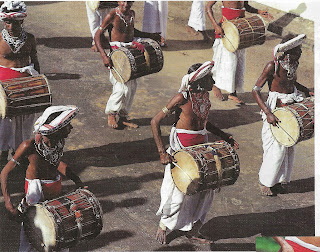

With its five processions — one each from the Dalada Maligawa and the four deistic temples — the Kandy Perahera is a kind of sacred grand opera performed in five acts by the light of the waxing midsummer moon and hundreds of torches fuelled by dried coconut kernels (and, these days, kerosene). Within its staggeringly huge cast of more than 3,000 which includes period-costumed highland chieftains, acrobats, highland dancers and weapon- and standard-bearers, as well as nearly a hundred caparisoned elephants — there are about 800 music-makers. Of these, 400 provide the music for the Dalada Maligawa Perahera, the grandest of the five pageants. Together they weave a fantastic tapestry of endemic music and sound with roots sunk deep in the past. As much as the spectacle, it is the living, vivid music of the perahera that conjures the magic of the time machine. The tumultuous tide of sound emanating from ancient instruments flows down the twisting medieval streets of Kandy and causes time to slow, stand still and finally turn back.

The musical score of the perahera is entirely unwritten. It must be learned by ear. It demands four varieties of drums, three other kinds of percussion and four wind instruments. The drums are played according to padamatra, stylized rhythmic scales with accented and soft beats and a varying tempo. Different padamatra are used for the martial gaman hewisi, the light and lively pantheru (tambourine) dance, the majestic, classical ves Kandyan dance and the electrifying ceremonial magul bere, which is played at the commencement of the pageant. Wind instruments play a tale, or tune, in a continuous flow of sound.

Sri Lanka’s traditional social structure has ensured the preservation of this unwritten musical heritage and the skills to perpetuate it through such institutions as the caste system and rajakariya land tenure. The caste system assigned specific mandatory trades, crafts and professions to socio-occupational groups. Passed on generation by generation in closed caste dynasties, these skills became honed to a high degree. The rajakariya literally “the king’s service”, a feudal land-tenure system that conferred leaseholds of arable land in exchange for services to the state and society has ensured that artistes, such as musicians who perform in the perahera, still enjoy such ancestral leaseholds today, though the rajakariya system was abolished early in British colonial times and tenants are no longer bound to make service payments.

The musical structures of the five processions of the Kandy Perahera are similar. The musician groups of the Dalada Maligawa Perahera comprise 80-100 hewisi martial drums, eight horanewa (small trumpets), two mahakombu (big trumpets) and two conch-shell blowers, 60 udekki drummers, 30-40 tambourine players, 20-40 leekeli (stick) musicians and 40-80 ves dancers attended by about 20 drummers. Interspersed in these groups, and among the savarang (whisk) and naiyandi folk dancers, are small drum units and cymbal players; two caparisoned elephants also walk with each group. Although the various musical groups may number more or fewer players from year to year, they always follow this basic pattern.

Pageants need clear paths. In the past, routes were cleared by whip-crackers. Modern traffic controls make whip-crackers unnecessary, but they still ply their ancient skill in the perahera, if only symbolically. As the procession leaves the temple courtyard and enters the city streets, the whip-crackers lash their two-metre-long ropes of coconut fibre and hemp. The knotted ends explode in loud, sharp cracks, adding an intriguingly anachronistic sound to the music of the perahera. The music itself is five-fold, from the five classical categories of musical instruments called the pancha turya. These are three classes of drums (played respectively with one hand, two hands or sticks), metal percussion (cymbals, tambourines, jingles and bells) and wind instruments such as trumpets and conch shells. The heavy preponderance of drums account for the percussive nature of perahera music. Pancha turya ensembles were considered essential trappings of pomp for Sri Lankan kings.

“The drums played in the perahera are the four classic Kandyan [highland] varieties geta bere, daula, tammattama and udekkiya,” explains Podisingho Malagammane, chief panikkiar, one of the four purveyors of music to the Dalada Maligawa perahera. “Among the drums, the geta bere is the truly endemic Kandyan drum and the one that all drummers and most other musicians must learn.” Malagammane, a perahera musician of the haute école, is descended from a rajakariya music dynasty in Nugawela, near Kandy. His musical heritage goes back several generations, to the time of the Kandyan kings. Tutored from the age Of 15 in traditional music and dancing by his uncle, Malagammane has been in the musical service of the perahera for nearly half a century. Even though perahera music must by now be in his blood, he says he’s still learning. Two of his sons, trained by him, are now skilled perahera musicians. The pride with which he mentions this offers a clue to how this mega-pageant has survived so robustly, long after the social institutions and contexts that nourished it disappeared.

Malagammane dwells on the finer points and intricacies of the geta bere. The slim-bodied drum has a tubular wooden shell “three hand-spans and three fingers” (about 71 centimeters) long, with tapering ends and a spare tyre bulge in the middle. It is named for the five geta (bosses, or knobs) girdling its shell, which is ideally made of red sandalwood, the preferred wood for all drums. As red sandalwood is extremely rare, geta bere and other drum shells are now made with a variety of other woods varaka (Artocarpus integrifolia), margosa (Azadiractaindica), gansutiya (Thespesia populnea), ehela (Cassia fistula, the Indian laburnum) and kitul (Caryota urens). “The wood of trees killed by lightning give the best ‘cry’ to a drum,” Malagammane says. “Maestros always seek out such wood for their drums.” The geta bere has two heads, each about 20 centimeters in diameter. The “master hand” head is of monkey-skin parchment, which gives a high, shrill tone. The other is ox-hide, which yields a deep bass sound. Skins of hare, deer and monitor lizards, collected from the bags of hunters, are used as parchments for other vatieties of drums. Both heads of the geta bere are mounted with an additional diaphragm of stout raw-hide called a kepum hama, which widens the tone range, and are tensioned with thick leather strapping across the entire length and girth. The ridged shell rolls sound in an echoing spiral, the double layer parchments give a range of clear and muffled tones, and the cross-roping tunes the heads to precise pitches. The geta bere is clearly musician-designed and constructed with a grasp of acoustics and the dynamics of sound.“Such a drum, so close to a musician’s pulse and heart, can only be played with the intimacy of the bare hands,” Malagammane concludes.

An old saying claims that a good drummer “can make the voice of his geta bere carry clearly over gauva” a distance of more than six kilometers. Some drummer families own antique red sandalwood geta bere drums that have been played for more than two centuries. Stone carvings at the 13th-century rock fortress at Yapahuwa and the 14th-century Gadaladeniya temple, near Kandy, depict the geta bere being played at rituals and pageants, which gives an aura of deep-rooted antiquity to this drum. The daula or daul bere is a stout cylindrical drum “two-and-a-half hand-spans” (or about 56 centimeters) long, with deerskin heads about 30 centimeters in diameter. It shell of ehela wood is embellished with oriental motifs in natural Kandyan lacquer hued vermilion, yellow and black. The daula drum heads are tensioned with cord braces and 12 small clips called ilium. Played with a kadippuwa (stick) on one head and by hand on the other, the daula bears a resemblance to the European tenor drum. During the reign of the Kandyan kings, skilled daula players were given a kind of feudal Grammy Award, ebony or ivory kadippuwa drumsticks mounted with chased silver or gold. These are treasured heirlooms in traditional drummer families today. The tammattama and the tiny udekldya are more folksy and homely than the geta bere and daula. They are played in a less rigid style and add a lilting touch to pera hera music. The tammattama is two hemi spherical kettle drums lashed together; one head is 25 centimeters in diameter, the other 20 centimeters. The smaller head yields a high tone, the larger one a dry, rattling sound. The drum is struck with two light, ringed sticks like dulcimer hammers.

The udekkiya, the smallest perahera drum, was originally used to accompany folk dances at the Kandyan court. Its pinch-waisted, hourglass-shaped gansuriya shell has heads of goatskin, with a cloth strap round its middle for tensioning them. Unlike all other perahera drums, which are worn on waist slings, the udekkiya is held aloft in one hand and hit with the other. Almost all perahera drummers are also trained dancers. “We dance to our own tunes,” jokes 45-year-old O.P. Karunadasa, who has served as a perahera musician for 20 years and is now a panikkiar of the Dalada Maligawa. “We also fashion our own drums, with some help from craftsmen. Each drummer becomes an expert on a specific kind of drum, but many can play all varieties, as well as other instruments.” Drums apart, many other instruments and artefacts make pageant music and sound. The sonorous, booming wail of the hakgediya the conch shell blown by the Hakgedi Rale (Official of the Conch) heralds the solemn moment when the relic casket is taken from its sanctuary and musically signals the start of perahera ritual proceedings. Two conch shells are played when the perahera is in progress. The large, cone-shaped conches come from Mannar, on the northwestern coast, and from South India. “Blowing the conch shell may look simple, but don’t fool yourself,” warns 62-year-old P.G.H. Ihalewela, another of the panikkiars, who embarked on his musical career as an apprentice to his father in 1948. “There is an art and a style to it. The conch has to be blown in a long-drawn, even crescendo — in unbroken, even blasts — and must lead the ear on to the dramatic outburst of the ceremonial magul bere drums. A good ear, good lungs and a theatrical style are essential.”

The pantheru (tambourine) players tap out gay, jingling, gypsy-like music on their large brass rings, threaded with seven sillu (cymbal-like discs), gracefully flinging them in the air to produce showers of melodious jangles. Udekki drummer-dancers, savarang (whisk) and naiyandi folk dancers all wear silambu, elliptical anklets of hollow brass with tiny musical jingles. In addition to this, ves dancers wear bangles, bracelets and an elaborate headdress, all of which produce cascades of light, effervescent musical sound with every movement. Drummers and dancers keep time with talampota, heavy, ringing brass cymbals with scooped-out centres. One of the smallest instruments of the perahera orchestra, the talampota controls the sounds and movements of the pageant in a stylized rhythmic framework.

Two important brass wind instruments the horanewa and mahakombuwa are played in the perahera, mainly with the drums of the march, the hewisi. The horanewa is akin to a small trumpet, just over 30 centimeters in length, and is cast in brass with a mouthpiece of ebony, ivory or buffalo horn. Inserted into the mouth piece is a reed of tender talipot palm leaf with seven wind vents, which produces a varied range of high-pitch notes similar to South Indian hautboys. The impressive mahakombuwa is a huge, curved brass horn resembling a tuba and has a deep, sepulchral voice. Two are played in the Dalada Maligawa perahera.

The leekeli (stick-play) musicians add a folksy harmony, as they strike out their clacking tunes and weave and unweave rhythmic patterns with the colored streamers trailing from their simple wooden instruments. The perahera musical repertoire also includes the harmony of the human voice. Sung accompaniments are always part of udekki, pantheru and leekeli performances and of naiyandi, savarang and ves dances. A chorus of five minstrels, the kavikara maduwa, accompanies the relic casket, singing the Dalada Sirita, a serenade of praise and homage to the Sacred Tooth Relic. Musicians dress in ceremonial haute couture when they play in the perahera — highly theatrical period costumes, worthy of grand opera. Long, white, red-edged, draped pantaloons (tuppotti), or ankle-length white waist cloths and scarlet cummerbunds, comprise the basic musicians’ ceremonial attire. Tight white turbans, threaded with red or gold braid, trail tassels at the back that punctuate the vigorous tosses and flourishes of the head made while playing. The varied accessories include ornately beaded collars, dangling ear ornaments, heavy silver or brass armlets and tinkling anklets.

Perahera musicians need plenty of stamina, as groups play (in relays) for at least three hours in the pageant. Rising above the varied and complex music of the perahera, is the clear, silvery sound of tiny bells, two of which are worn around the necks of each of the nearly 100 pageant elephants. Cast in an alloy of iron, brass, copper, silver and gold to give a prescribed musical pitch, they add an exquisite touch to the light, fantastic music of the perahera, a return across the centuries into another time.

Comments

Post a Comment